Maybe it’s just me… but do you ever wish that Tacitus was still around?

This week, for instance… There’s been all kinds of serious and dramatic politicking going on in the UK, but what caught my eye – and what would, I suspect, have delighted Tacitus too – was the huge public uproar about a politician’s posture. It’s all just so very… Roman.

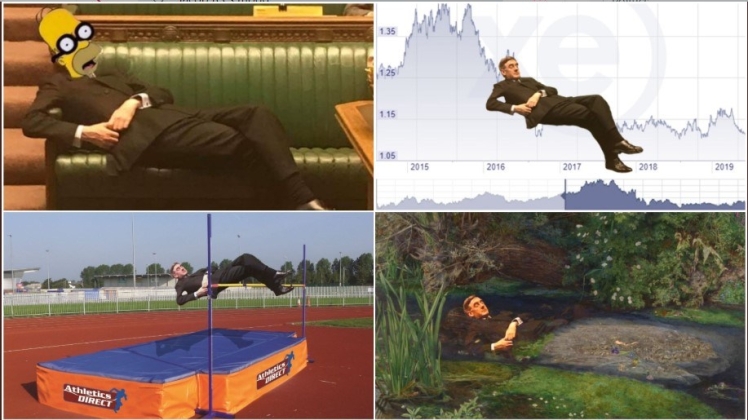

In case you’ve been doing something more useful this week, here’s an outline… MP and Leader of the House Jacob Rees-Mogg (now renamed Rees-Smug by the Internet) was called to account by another MP for his ‘contemptuous’ lounging in Parliament. The image lit up social media and generated disapproving headlines across the country for days.

Rees-Mogg’s posture was immediately linked by the media and by other MPs to social class, personal wealth, moral failings, contempt for the workings of democracy, and a host of other real or imputed qualities. It’s been fascinating to watch.

The instinctive outrage generated by the sight of a privileged person failing to sit up straight turns out to be a powerful force. Words like ‘slouching’ have been used by the media. I don’t think I’ve heard an accusation of ‘slouching’ since I was one of the Ten Green Bottles in the school talent show.

(In case you’re wondering, I didn’t “accidentally fall”: I was pushed.)

There’s a visual code which is expected to be followed in formal situations, which encompasses a whole range of elements from posture to dress and even expression – and we’re only really aware of it when somebody flouts it. Then people are horrified, appalled and insulted: it’s experienced almost as a personal affront.

As a teacher of mostly Roman stuff, I’d like to find a way to bottle that feeling of outrage so that I can bring it out whenever I need to explain Roman visual codes to people. Yes, we have an intellectual understanding of – for instance – Cicero’s verbal sketches of the people he’s trying to vilify, or the fact that Nero’s appearance on stage went against Roman convention. But we don’t feel that same sense of insult, that gasp-worthy feeling of wrongness, which we experience when someone violates our own social codes. It’s like the way we experience a joke: if it needs to be explained, then it isn’t funny. If outrage needs to be explained, then it’s not actually being felt.

The other fascinating thing about ‘Slouchgate’ is the way that people have tried to interpret it. Psychologists online have explained that Rees-Mogg’s posture is intended to project ease and comfort to deflect attention from his strong discomfort with the situation. Social commentators are talking about the training in projecting superiority which is supposedly given at Eton. Some people are talking about Rees-Mogg sending a message through his posture about the tedious impossibility of resolving the Brexit problem. Other people are pointing to Rees-Mogg’s political ability and asking what the ‘plan’ is behind his actions. Is there a message here – and if so, what is it?

And that’s why I miss Tacitus.

Forget votes and party politics: this is the spectatorial politics that Tacitus understood. He excelled at pointing out the messages that were sent by powerful people through the way they chose to present themselves – and also the ways in which those messages could be misunderstood, subverted or used as political ammunition against them. And then he could twist both sides to get his own point across.

Take, for instance, his epitaph on Sallustius Crispus, another conspicuous lounger, in Annals 3.30:

Crispus, a knight by extraction, was the grandson of a sister of Gaius Sallustius, the brilliant Roman historian, who adopted him into his family and name. Thus for him the avenue to the great offices lay clear; but, choosing to emulate Maecenas, without holding senatorial rank he outstripped in influence many who had won a triumph or the consulate; while by his elegance and refinements he was sundered from the old Roman school, and in the ample and generous scale of his establishment approached extravagance. Yet under it all lay a mental energy, equal to gigantic tasks, and all the more active from the display he made of somnolence and apathy. Hence, next to Maecenas, while Maecenas lived, and later next to none, he it was who sustained the burden of the secrets of emperors. He was privy to the killing of Agrippa Postumus; but with advancing years he retained more the semblance than the reality of his sovereign’s friendship. The same lot had fallen to Maecenas also, — whether influence, rarely perpetual, dies a natural death, or there comes a satiety, sometimes to the monarch who had no more to give, sometimes to the favourite with no more to crave.

(Loeb translation)

Here’s a man born into wealth and privilege, who makes a show of ‘somnolence and apathy’ (somnum et inertiam in the Latin). All familiar stuff from the media this week. But Tacitus uses Crispus to expose a hidden layer of influence that exists beneath the official structures of power and the formal offices held by senators, and which in many ways completely invalidates the whole cursus honorum. Crispus may look like a rich and idle layabout, but he’s the one who knows where the bodies are buried. Then Tacitus moves on from the revelation of a secret sub-government to make a pointed comment about the transience of a power that only lasts as long as somebody wants something: the very opposite of the duty-dominated pietas which is supposed to underpin Roman public life.

Tacitus manages to criticise Crispus, Maecenas, successive emperors, the Senate and pretty much the whole of society in one go; the only person who comes out of this looking good is the historian Sallust. And he accomplishes all of this in a single paragraph which looks like an obituary.

So yes, maybe the papers and the internet have been blowing Rees-Mogg’s slouching out of all proportion. But if Tacitus were here, he’d be doing the same thing: only more efficiently, more cleverly and with much more style.

We’re managing ok without him, though. As a culture we may not have Tacitus’ knack for finding the perfect epigram, but who needs sophistication when we’ve got internet memes…?

This week’s links from around the internet

From Classical Studies Support

A classicist in Paris – Emily Peacock

News

Suggestion for Elgin sculpture swap – The Guardian

Sculpture plans rejected – Greek Reporter

Mosaic to be reburied – The Telegraph

Lessons for Boris from Augustus – The Guardian

Mel Gibson to play Odysseus – Geeks WorldWide

The dangers of Latin spells – The Independent

Comment and opinion

Ovid’s Medusa in art – Winds & Waves

Building Latin vocabulary – In Medias Res

Learning Latin conjugations – Kiwi Hellenist

Myth and bad feminism – Eidolon

The vengeful Amazon – Reboot the Past

Subverting whiteness – Hyperallergic

Animating Thucydides – Institute of Classical Studies

7 sculptures you need to know – Artsy

Roman Norfolk – North Norfolk News

Learning Etruscan – CREWS Project

Autism and studying Classics – Mythology and Autism

The significance of wine in Greece – Classical Wisdom Weekly

Project Fear and Thucydides – Sphinx

Mythical wife guys – Idle Musings

Honest Latin mottos – McSweeney’s

Podcasts, video and other media

Diogenes the punk rocker – History on Fire

The misunderstood Elagabalus – Emperors of Rome

Athens on the offensive – The History of Ancient Greece

Romans and barbarians – The Partial Historians

Early Rome – History Machine

The death of Agrippina – Life of Caesar

Other stuff

Homer event in London – The Roman Society

Legonium Latin book on sale – Abbey’s Bookshop [it’s on my Christmas list!]

Undergraduate journal inviting submissions – Philomathes

Loving the ‘principal parts of παιδεύω’ jingle! Very nifty. And the ‘order of adjectives’ list is intriguing. I wonder if such orders (and in what permutations) exist(ed) in other languages. Not, presumably, in inflected languages with flexible word orders. Hmmm…

LikeLike